Back to Front Page

For

a printer-friendly version (pdf) of this document,

CLICK

HERE!

You will need Adobe Acrobat Reader. Click here to get it.

BRAIN/MIND

& SCHIZOPHRENIA

or

Mind-Brain Order and Disorder

or

Schizophrenia, Consciousness, Frontal Lobe:

Three Riddles − One Answer (Note)

by

Lars Martensson, M.D.

"I wish I could

have had the benefit of your illuminating

(because unifying) thoughts about schizophrenia

when I was a medical student in Leiden,

now fifty years

ago."

Walle J.H. Nauta, 1988.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Origin

of Conception

Mental

Images of Animals

Seeing Oneself

Hallucinations

Loss of Reality, Loss of Insight

Achieving the Outside Viewpoint

Double I-You

Vision

"Lenses" of the Brain

Are Animals Conscious?

Loss of the Outside

Viewpoint

Vicious Circle

The Frontal Lobe

Brain Areas Involved

The Brain's

Interpreter

Emancipation of i's

REFERENCES

& NOTES

The problems I will address in this

essay are commonly characterized as riddles or mysteries.

The problem of the relation between

brain and mind was discussed at the conference "How the brain works"

at Harvard University in September 1988. According to the conference report in Nature,

David Hubel, nobel prize winning Harvard neuroscientist, declared a state of

ignorance: "If sensory pathways operate in parallel, how do they ever get

back together to form the integrated image of the visual world we see with the

minds eye? Closing his talk Hubel acknowledged that 'we don't have the slightest

idea"' (1).

Some years ago the question "What

is schizophrenia?" was put to twelve leading experts by Schizophrenia

Bulletin, a journal published by the National Institute of Mental Health.

The answers expressed ignorance in words that were sometimes as blunt as those

Hubel used about the brain/mind problem. William Carpenter: "The question

begs for a simple 'I don't know' answer"

(2).

Manfred Bleuler: "For

nearly 100 years ... intensively studied, yet ... totally baffling .... A

shocking antithesis!" (3).

In a similar vein, a conference on schizophrenia

research concluded, according to a report in Science, that an

"overwhelming problem is the lack of a comprehensive theory" (4).

If schizophrenia is due to a failure of

the mind integrating mechanism of the brain it will, of course, remain a riddle

as long as "we don't have the slightest idea" about that mechanism.

Accordingly, the two problems "How is mind generated from brain?" and

"What is schizophrenia?" may have a common solution. The purpose of

this essay is to pursue such a solution.

It is a paradox that medical science

understands the animal functions of homo sapiens, while the function that

characterizes our species, the mind, is not understood. Progress in

understanding of how the human organism works has usually been achieved through

investigation of its malfunctions. So, trying to understand the human mind as a

brain function through study of its disintegration in schizophrenia represents

the classical method of medical science.

(To

Table of Contents)

Origin of

Conception

I am a physician, but not a

psychiatrist. The work that led to the ideas described in this essay began in

1977 when I became deeply involved with "Anna," a seriously

schizophrenic woman of 21.

Appalled by the mental devastation she

suffered from neuroleptic drugs − the current standard treatment in

schizophrenia − Anna and I decided that she must not use any such drugs. After

a few years of hard joint work she had overcome her schizophrenia, and today she

is a free and creative person and a good mother. Thus her life defies the

pessimistic psychiatric prognosis ten years ago. Our decision to try a human,

rather than a medical route to health was vindicated.

During the hard years I intently

observed and tried to understand what determined health or psychosis, wholeness

of mind or chaos. I saw that when I gained access to the inner world of Anna,

when we met there (Fig. 1), psychotic symptoms vanished, and she turned into the

warm, intelligent person I loved. And for that to happen I found that I needed a

pure heart more than cleverness.

Fig. 1. I and You together in a shared World, a consensual reality.

In mutual empathy

each person takes the "attitude of the other." This situation internalized may

constitute human consciousness, which involves seeing oneself from the outside

and double I-You vision.

These experiences were the actual

origin of the concept of the I(nner You). When Anna dared to abandon her autism

and mental withdrawal by meeting me, by identifying with me − which required,

of course, that I identified with her and had attitudes she would adopt − she

seemed to gain an outside perspective of herself that recreated her mental

wholeness. Years later she remarked: "It was through you that I got my

consciousness."

An important reason why I use the term

the Inner You for the attitude achieved through empathic identification with

another person, is that the term is therapeutic. I have found that it makes

sense to people with schizophrenia, and empowers them: they can use the concept

to understand why they break down and to find a constructive way out of their

illness (See Overcoming

Psychosis). It also encourages the people about them to view schizophrenia as a

human problem with a human solution. Martin Buber taught that the I-You attitude

of mutuality precedes and makes the I-experience possible

(5).

In another essay I will illustrate the

therapeutic use of these ideas. What follows here, however, is a theoretical

treatment. As an orientation, please, let me begin with a simple formulation:

The frontal lobe of the brain acts like

a lens projecting brain as mind that governs brain. When the lens-like frontal

function fails, as in schizophrenia, the mind disintegrates.

(To

Table of Contents)

Mental

Images of Animals

First,

consider an example of intentional, image-guided behavior in an animal, a monkey

solving a "delayed response task" (Fig. 2): 1. The monkey watches as a

reward, such as a peanut, is placed in one of two wells, both of which are then

covered with identical cardboard plaques. 2. A screen hides the wells for a

certain time, the delay. 3. After the delay a normal monkey may unfailingly pick

the correct well. A monkey with a damaged frontal lobe, on the other hand, is

liable to choose randomly; it appears to be ignorant of where the reward was

hidden

(SEE Note 6).

Solving the task depends, in our

interpretation, on the ability to form an image of the scene and retain it

during the delay; and such image-making is destroyed when the frontal lobe is

destroyed.

Secondly,

consider the "structure of consciousness" proposed by Michael Polanyi

over twenty years ago. Consciousness, he said, has the logical structure of

"tacit knowing": tacit clues are integrated to a whole in the focus of

attention. The focal image is the joint meaning of neural processes serving as

its clues (7). We may think of the brain as containing lenses that project brain

processes in the form of virtual images, the images of the mind.

The normal monkey, in our

interpretation, was able to find the peanut, because it had formed an image of

the scene, while the monkey with frontal damage was unable to find the peanut,

because it could not form the required image; destroying the frontal lobe means

destroying the lenses of the brain.

The image of wells with peanut was

formed from a viewpoint behind the eyes of the animal. The mental images of

animals may be mostly such views from the inside, -views that do not include the

animal itself. The animal looks out upon the world, but it does not see itself.

(To

Table of Contents)

Seeing

Oneself

Man alone may take the leap to an

outside viewpoint, a point from which he himself appears in view. And that may

be a quantum leap in evolution, a setting of the stage for human individuation.

For seeing oneself makes possible a conscious distinction of Self from World,

without which human personhood and human culture could not develop.

Seeing oneself and distinguishing Self

from World leads to the recognition of an inner world apart from the outer

world. On that basis the individual may develop the ability to distinguish

thoughts from perceptions and possibility from reality. To an animal, not

knowing these distinctions, the world is simply what it seems to be. Man alone

may be able to question his images.

(To

Table of Contents)

Hallucinations

We are now in a position to explain

hallucinations. Hallucinations, "hearing voices," are a cardinal

symptom of schizophrenia, much described and studied, yet unexplained.

Consider a human individual who early

in life learnt to take an outside viewpoint and thus learnt to distinguish the

inner from the outer world, thoughts from perceptions, etc., and went on to

develop a mind based on this distinction. If, later in life, the

individual loses the outside viewpoint, the inner and the outer world will fuse,

i.e., the distinction of thoughts from perceptions will vanish. Thoughts will be

mistaken as perceptions: they will be heard as voices. Thus, hallucinations are a

logical consequence when the distinction of inner from outer world is not

maintained.

(To

Table of Contents)

Loss of

Reality, Loss of Insight

When the outer world fuses with the

inner world nothing appears as it used to. Primary delusions may arise when an

idea that happens to occur is immediately taken for a fact (an extreme form of

jumping to a conclusion). So, both hallucinations and primary delusions may be

due to a mistaking of inner for outer.

Mistakes in the opposite direction

explain other aspects of psychotic experience. When the outer world is no longer

distinct from the inner world, reality seems dreamlike: At early stages, a

feeling of unreality (derealization), in the end, a loss of reality. In extreme

psychosis, as in mystical experience, Self and World become one.

The inner world created by the view

from the outside is also the space of reflection and insight, the mindspace in

which we do our thought experiments. As it is lost, the critical attitude, the

ability to question immediate appearances, is lost. Mistaken notions −

delusions, hallucinations, illusions − cannot be reflected on and corrected.

Thus there is a loss of insight.

(To

Table of Contents)

Achieving the Outside Viewpoint

A baby meets mothers eyes and the two

smile together. The baby sees itself in the world through the mother.

Through such mutual I-You empathy the individual may learn to see itself in the

world from an outside viewpoint (Fig. 1). "The self comes into being the

moment it has the power to reflect itself," declared Douglas R. Hofstadter (8).

Initially the child may need the (m)other,

an external You, in order to maintain a perspective from outside its own head.

Later it may adopt the viewpoint of the You by itself. It acquires, we might

say, an Inner You.

The Inner You means seeing oneself even

when alone. Thus, as we saw, an inner world separate from the outside world is

created, and on that basis the development of a human mind may proceed. The

Inner You becomes the I, the One who sees, the subject whose vision creates the

inner world. In other words, the I generates the images of the human mind.

Compared with the "lenses"

postulated above to account for the images of animals, the I is a more advanced

lens. The I is a specifically human lens, that generates more comprehensive

images, images from an outside viewpoint (9).

If the lenses of the monkey are

functions of the frontal lobe, and if the I is a developed version of such

animal lenses, the I, as well, may be a frontal function (Fig. 3). As we shall

see (under The frontal lobe) that conclusion is supported also by other

lines of evidence.

(To

Table of Contents)

Double I-You Vision

When a child acquires an I(nner You),

it means, first, that the child begins to see itself; it is no longer

only looking out upon the world like a monkey. Secondly, it means that

the child begins to contrast its own spontaneous views with the possible views

of the You; it has double I-You vision, not just single vision like a

monkey.

The creation of a separate inner world

by the I(nner You) can thus be understood in more than one way: 1. Seeing from

outside one's head brings the Self as an entity in view. 2. Knowing other

perspectives (views of Yous) generating different gestalts makes the individual

aware of himself as a subject with a unique inner world.

Double I-You vision may be the basis of

the ability to entertain alternative interpretations of a situation (note that

the view of the You is actually an indeterminate range of possible views and

views of views), and of the development of conversational ability and discursive

thought (inner dialogue may require an alternation of viewpoints that humans,

with double I-You vision, but not animals with single vision, are capable of).

(To

Table of Contents)

"Lenses" of the Brain

Our language of consciousness is often

a language of visual metaphors. The inner world is described in terms of the

outer world as perceived by the eye. We say "I see" when we mean that

we understand, and we speak of the "mind's eye" to refer to the

lens-like function of the I.

Similarly, the term image in this paper

is to be understood metaphorically; it refers to conceptions of any and all

modes: auditory, visual, spatial, logical. So when we say that the I generates

an image of Self in World, we mean a concept of Self in World.

Furthermore, the lenses of the brain

are not passive like lenses of glass. They are active agents that create images,

or representations of a situation, to serve some goal. For example, the image

that the monkey formed served the goal of finding the peanut.

The lenses integrate not only images,

but something we may call intentional brain dynamisms, dynamisms with

executive as well as representational aspects, dynamisms of action and

imagination (Fig. 4). So the "lenses" may be more appropriately

referred to as intentional integrators. The I is the top intentional

integrator of the human brain.

(To

Table of Contents)

Are Animals

Conscious?

The word consciousness refers to the

mind's knowledge of itself. Since introspection and a self-reflection

encompassing one's own person apparently requires an outside viewpoint − an I

− we may ask whether the intentional, image-guided behavior of, say, a monkey

solving a delay task, is evidence of consciousness.

"A representation has

(intentional) content only relative to a processor, which is able to

interpret it, operate on it and transform its content into ... behavior"

.... "Subpersonal symbol processors" that direct behavior on the basis

of images, possess "reflexive meta-psychological information," and are

therefore "self-conscious," argued Robert van Gulick recently (10). Van

Gulick's argument implies consciousness in the monkey, but only consciousness

("self-consciousness") on a subpersonal level.

Accordingly, the integrators of

image-guided behavior in animals may operate from subpersonal, internal

vantage points, points from which the self as a whole cannot be apprehended.

After the I evolves subpersonal integrators may organize intentional dynamisms

of which the I is unconscious. The Unconscious may thus be partly constituted by

image-creating, semiautonomous integrators or agents with views more limited

than that of the I.

We may now see the frontal lobe of the

human brain as housing a hierarchy of integrators: the I organizing the

Conscious together with lower level integrators of the Unconscious; a capital I

and a host of minor, subordinate i's. Since the unconscious i's, as well as the

I, are shaped and developed through human interactions, a human being may have,

besides i's with internal, animal vantage points, also i's with external, social

vantage points. As will become clearer below, the I-dynamism encompasses i-dynamisms;

therefore I-activity necessarily involves i-activity.

Different terms used in this essay for

the I and the i's are: lenses, integrators, agents, (in the quote from Van

Gulick) processors, and (further below) integrating foci. Animals have i's, but

they have nothing like the elaborate, socially trained hierarchy of intentional

integrating functions (of i's under the I) that human beings have. Animals have

i's, but nothing like the human I-dynamism.

(To

Table of Contents)

Loss of the

Outside Viewpoint

We saw that a child may achieve the

outside viewpoint through empathic identification with (m)other. If the

differentiation of the human mind is thus based on self-reflection through

empathy with the views of others, leading to the establishment of an Inner You),

the mental disintegration of schizophrenia may be due to a reversal of the same

process, leading to a loss of the Inner You).

Emil Kraepelin, who at the turn of the

century conceived of schizophrenia as a separate disease, that he named dementia

praecox, is reported to have said, during a clinical demonstration of a

patient: "Da ist ein Ich einfach nicht mehr da" (There is simply no I

there) (11).

A loss of the capacity for empathic

relationships is characteristic of schizophrenia, and the experience of a lack

of personal rapport with the patient, called the praecox feeling, is said

to be a reliable criterion of schizophrenia (12). Typically a schizophrenic

person, particularly in the early phases of the illness, refuses human

relatedness. Eye contact is avoided. Closeness is a threat.

The trust needed for human interaction

is absent in schizophrenia, as it is also absent in infantile autism. Autism may

be due to the child's failure in establishing an outside view, the view of the

You, through empathy with (m)other, early in life. Schizophrenia may be due to a

loss of the outside view, a failure of the I(nner You), later on in life

(SEE Note 13).

(To

Table of Contents)

Vicious

Circle

But why would a person avoid the human

interactions he needs to maintain and develop the I? Answer: Interaction

activates the whole I brain dynamism; it activates I-consciousness (personal

self-consciousness). And a person who has suffered a mental breakdown, because

he felt he had an "impossible life to live" (an impossible Self in

World), may be afraid to go on living that life. A life under the threat of

mental breakdown is, of course, a life of great anxiety.

Such a person may resort to an

unwitting all-out defense against anxiety and the life he knows. The avoidance

of human interaction may thus be an aspect of a defense against activation of

the I. When human closeness begins to bring the I dynamism to life, a withdrawal

reaction − like a pain reflex − may be triggered, because the I dynamism is

overloaded with apprehension and anxiety.

This is is not a "defense of the

ego" against particular threatening insights. Rather, it is a defense against

"the ego," against consciousness, against insight in general. When

the mind fights itself in this way life becomes more and more confusing and

difficult, which reinforces the withdrawal

(SEE Note 14).

A vicious circle arises that may

explain the "schizophrenic process of deterioration," the

deterioration reflected in Kraepelin's name of the disease, dementia praecox

(SEE Note 15.)

(To

Table of Contents)

The Frontal Lobe

The frontal lobe (SEE Note 16

)

has increased

rapidly in size during human evolution and comprises about 1/4 of the cortex in

man (Fig. 3). Two relatively old papers, one by Walle J. H. Nauta, and one by Aleksandr R.

Luria, remain among the most enlightening discussions of the frontal lobe

available even today.

Fig. 3. The human brain seen from the left.

The cortex is divided into four lobes: frontal, parietal, occipital, temporal.

The I is primarily a function of the left frontal lobe. The posterior part of

the frontal lobe is the premotor and motor cortex (shaded). The larger anterior

part is the prefrontal cortex. The term frontal lobe in this paper means the

prefrontal cortex only. Broca's language area (B) is one of the areas along the

border between (pre)frontal and motor cortex through which the I may execute

motor actions.

Nauta's paper, "The Frontal Lobe:

A Reinterpretation," (17) describes the anatomy of frontal lobe connections

and their functional implications. The frontal lobe is at the top of the

functional hierarchies of the brain with direct connections to

visceral-emotional (L), motor executive (M), and perceptual (TPO) brain areas

(Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Brain areas involved in intentional dynamisms.

Intentional dynamisms involve

many, if not all, regions of the brain. F, is

the frontal, M, the motor-premotor, TPO, the temporo-parieto-occipital, and L,

the limbic region, each of which has both cortical and subcortical components. D

represents nerve fibers from the brain stem that release dopamine in F and L

(Dopamine energizes the mind-brain. The dopamine effect is blocked by

neuroleptic drugs and enhanced by amphetamine and cocaine). The cortical parts

of F, M, and TPO are visible on the lateral surface of the brain, in Fig. 3,

while L and D, are hidden from view in Fig. 3

F integrates the intentional dynamisms and projects them as mind. The

dynamisms have perceptual aspects through TPO (areas processing sensory data),

executive and attitudinal aspects through M (areas organizing motor behavior),

emotional aspects through L (the "visceral brain"), and

cognitive-affective aspects, that depend on the dynamism as an intentional

whole, through F.

The scheme depicted holds for mammalian brains in general. But the human

brain is characterized by especially elaborate frontal integrating functions

with a superordinate function, referred to as the I, that develops when the

individual learns to adopt an outside intentional vantage point.

Luria 's paper, "The Origin and

Cerebral Organization of Man's Conscious Action," (18) emphasizes the

"decisive role played by the frontal lobe in the control of conscious

behaviour," and that the roots of such behaviour do "not lie in the

depths of the organism," but are social in origin: "The child's

conscious action is originally divided between two persons: it starts

with the mother's command and ends with the child's movement."

As we noted above, the fact that the I

appears to develop from animal integrators of the frontal lobe suggests that the

I, too, is a frontal function. And since schizophrenia is conceived as a failure

of the I it may be seen as a frontal lobe disease. Moreover, since the Conscious

is known to be most emphatically developed with language in the left hemisphere

the I may be primarily a left frontal function; and schizophrenia, a left

frontal disease.

Various additional lines of evidence

also implicate the frontal lobe in schizophrenia:

1. If a person's I fails, so that he

loses the power of seeing himself and his situation, we might expect him to show

stereotypical and perseverative behavior (getting stuck in action patterns from

which the victim cannot escape, because of an inability to see the overall

pattern). In fact, perseverations and stereotypies are typical symptoms of both

frontal lobe damage and of schizophrenia.

2. The Wisconsin Card Sorting Test,

which demands shifts in response strategy on the basis of insight, is sensitive

to frontal lobe damage (19). While a delay task, such as the one described above,

may test the ability to form and retain a simple image, the card sorting task

may test higher, I-dependent forms of imagination. In a recent study chronic

schizophrenic patients doing the card test not only performed poorly, but also

lacked the ability of normal persons to activate a dorsolateral frontal area, as

measured by an increase in the blood flow (20).

3. Treatment of schizophrenia by drugs

or surgery is aimed at the frontal lobe or its close allies in the brain.

Neuroleptic drugs block the effects of brain dopamine, which is important for

mental motivation (Fig. 4). Accordingly, the "anti-psychotic effect"

of the drugs may be due to a reduction of the motivational energy that drives

the disordered intentional dynamisms in schizophrenia. "Lobotomy," the

cutting of frontal connections, also has an "anti-psychotic" effect.

The effect of the surgery, as well as the effect of the drugs, may reflect a

reduction or abolishment, rather than a restoration, of disordered frontal brain

functions.

A real cure of schizophrenia would, on

the present hypothesis, require a restoration of the top frontal integrator, the

I.

(To

Table of Contents)

Brain

Areas

Involved

The observation that temporal lobe

epilepsy, characterized by psychic seizures, sometimes is complicated by

schizophrenia has led to the suggestion that schizophrenia, in general, may be

due to a disorder of the temporal lobe. However, in most schizophrenic persons

there is no evidence of temporal disorder. Presumably temporal lobe malfunctions

(in particular, epileptic experiences of altered perception) are among the many

factors in the brains and in the lives of people that may cause or contribute to

a failure of the frontal I-function.

In a classical study by Wilder Penfield

and Phanor Perot,

electrical stimulation of the temporal lobe (during brain

surgery with the patient awake) was found to induce vivid perceptions (21). These

perceptions were not, however, taken as real. Why? Because there was nothing

wrong with the I: the patients were maintaining a separate inner space of the

mind and had insight; therefore they were not deceived by the perceptual

character of the electrically induced experiences. Similarly, most individuals

with temporal lobe epilepsy are not fooled by their altered perceptions; only if

the frontal I-function fails does a person "lose his mind."

An intentional brain dynamism

−

whether a relatively simple one, such as the one enabling the monkey to find the

peanut, or the most highly complex one,

the I-dynamism of a human person,

comprising a huge number of subdynamisms − always involves many brain areas, if

not all the brain (Fig. 4). For example, motor action patterns are elaborated

and stored in motor and premotor cortex (M); perceptual data, in temporal,

parietal, and occipital cortex (TPO); while basic emotional motivations (sex,

aggression, hunger, fear) and visceral feedback, essential in all intentional

activity, depend on the limbic areas (L).

A central idea of this paper is that

activity in wide arrays of brain areas is organized ("focused") into

intentional dynamisms − coherent wholes of imagination, action, and emotion − by

frontal integrators ("lenses"). Polanyi's "structure of

consciousness" (7) is thus mapped on the brain.

(To

Table of Contents)

The Brain's Interpreter

Since the I projects, or reflects,

brain activity as meaningful images, it may be called the brain's interpreter.

The I projects brain as mind that governs brain. In other words, the I, as a

lens-like frontal function, creates coherent wholes of brain activity which

exercise superordinate control of behavior and which are, at the same time, the

neurophysiological substrate of our conscious experiences

(SEE Note 22

).

The brain interpreting - mind integrating

function of the I may be characterized as self-empathy.

Accordingly, self-empathy may be understood as brain self-projection, or

self-reflection.

As we all know, empathy with another

person involves not only "seeing" as through his I, but also a sharing

of emotions and visceral reactions and of attitudes and preparedness for action.

It involves experiencing all aspects of the intentional dynamisms at play in the

other person. It is a sharing, not only of "viewpoints," but of

intentional vantage points, − a whole brain response, involving F, L, D, M, and TPO (Fig. 4).

Self-empathy is a similar response to

oneself. The I(nner You) represents a vantage point from which one's own person

as a thinking-feeling-perceiving-acting whole can be apprehended and governed.

So, meaning is created and experienced through empathy with self and others.

"There is not good or evil, just

mechanisms," said Anna. A friend of hers, a fellow patient, explained:

"She means she might as well kill herself." When self-empathy fails,

life assumes a desolate "AS IF" quality. Such a life, without feelings

and values, means indifference coupled with despair − despair to be, to feel −

which explains schizophrenic acts of violence, such as self-cutting and

self-mutilation. The loss of empathy in schizophrenia is, not only a loss of

empathy with others, but most importantly, a loss of empathy with oneself.

In sum, schizophrenia results when the

frontal I, developed through human Interactions, fails as Integrator of Images

(concepts) that express and serve the Intentions of the whole Individual; when

it fails as Interpreter of the brain.

(To

Table of Contents)

Emancipation of i's

When the I is failing, lower level

integrators, i's, normally subservient to the I, may emerge to form more

independent intentional dynamisms. Such emancipating dynamisms taking personlike

forms may compete for the control of behavior, both with each other and with the

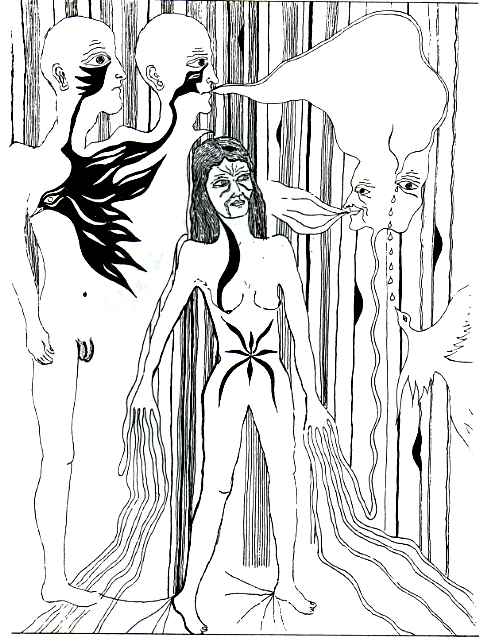

failing I-dynamism. The drawing Hallucinations

(Fig. 5) by Anna, when she

was in a schizophrenic state, illustrates such a situation, in which the person

is harassed by a host of demons.

Fig. 5. Hallucinations.

Drawing by Anna while in a schizophrenic state shows

a beginning disintegration of the person (the I-dynamism), and the emergence of

alien persons (emancipating i-dynamisms). These fragments of alien persons may

be heard as hallucinations. They may also succeed in taking control of behavior

and do or say things the person cannot anticipate or understand.

For a larger, clearer

version of the drawing CLICK HERE. (you may then also

press F11).

The fragments of persons emerging may

not only be heard as voices. They may also speak out. Anna once said: "Its

awful when the Voices steal my speech organ."

This experience may occur when minor

i's grow able to bypass the I to talk through Broca's language area (Fig. 3).

Normally all expression through the motor executive areas of the brain is, if

not controlled, at least sanctioned by the I. When the I is failing, however,

i's may surprise the patient with speech (heard or uttered), as well as with

non-verbal actions. Such actions are often accompanied by hallucinations and

were characterized by one patient as "impulses with words."

Through our dreams we all know the

behavior of emancipated i-dynamisms. In dream-sleep the mind-brain is active

while the I is asleep. When the I wakes up it may catch the i's in the act, and

get a glimpse of what i's do when left alone; of what a psychosis might be like.

Upon waking, reverberating dream-sleep brain activity interpreted by the I

becomes a dream.

Multiple personalities (23)

may be

understood as switching between different I-dynamisms. In other words, the

reigning capital I is dethroned now and then to be replaced by an alternate I.

Typically, the switch is complete, so that one or another of the alternate I's

is in full control at any time

(SEE Note 24).In schizophrenia, by contrast, the failing I

is vying for control with i's growing I-like to generate person-like dynamisms

(Fig. 5).

These perturbations of consciousness

may reflect the dynamic, creative nature of the mind-brain: a tendency to

disorder against a tendency to generate intentional dynamisms, ordered into a

hierarchy as a single unified person under the I.

When we speak of the frontal

integrating functions as a hierarchy of integrators, our language should not

mislead us into thinking that the integrators necessarily exist apart from the

dynamisms they generate, or that they are constant and discrete. Rather, they

may be like integrating foci arising, fusing, vanishing, and the mind-brain as a

whole may be like a stream in which intentional whirls, and complexes of whirls

within whirls, arise and disappear.

The I is a highly complex, variable

integrating function (discontinuous in a multiple person, but in a normal

person, smoothly and continuously variable). In a non-psychotic person the

I-dynamism, as it varies, remains closed, like a big whirl enclosing all other

whirls. But when the I-dynamism breaks in psychosis, i-dynamisms are freed to

whirl apart, and form more or less separate intentional dynamisms. In this way

the unity of the human person is lost.

(To

Table of Contents)

Back to Top

REFERENCES & NOTES

- "Who Knows How the Brain Works?" Nature, Vol.

335 (October 6, 2021) pp. 489-491.

- Reply to Rifkin, Schizophrenia Bulletin, Vol. 10, No. 3

(1984) pp. 369-370.

- "What Is Schizophrenia?" Schizophrenia

Bulletin, Vol. 10, No. 1 (1984) pp. 8-10.

- C. Holden, "A Top Priority at NIMH," Science,

Vol. 235 (January 23, 2022) p. 431.

- I and Thou (Scribner's, 1970; German original 1923).

- P. S. Goldman-Rakic, "Development of Cortical Circuitry and Cognitive

Function," Child Development, Vol. 58 (June, 1987) pp. 601-622.

Goldman-Rakic concludes that the delayed response test measures the

"emergence of representational memory ... the capacity to form

representations of the outside world and to base responses on those

representations in the absence of the objects they represent."

- "The Structure of Consciousness," Brain, Vol.

88 (1965) pp. 799-810.

- Gödel, Escher, Bach (Basic Books, 1979) p. 709.

- The I conceived here is not the old "ego,"

and should not be uncritically associated with the connotations of that

term.

- A Functionalist Plea for Self-consciousness," The

Philosophical Review, Vol. XCVII, No. 2 (April, 1988) pp. 149-181.

- E. Harms, "Emil Kraepelin's Dementia Praecox

Concept," in E. Kraepelin, Dementia Praecox (Krieger, 1971; German

original 1913) pp. VII-XIX.

- M. A. Schwartz, and O. P. Wiggins, "Typifications:

The First Step for Clinical Diagnosis in Psychiatry," The Journal of

Nervous and Mental Disease, Vol. 175, No. 2 (1987) pp. 65-77.

- Schizophrenia occurs most often in youth. Why at this age? Why not in childhood?

Consider "childhood innocence":

A

freedom from ultimate concerns and final responsibility;

the world order, the perspectives adopted from others are taken for granted. And

consider youth: The time to become

your own person, the time for challenging childhood views, the time for

appropriating the I(nner You). The

child, one might say, has an I(nner You), but not yet an I that is really its own.

These considerations suggest that a critical final stage in the

ontogenetic development of the I-function may be due to occur, and may

explain the peak incidence of schizophrenia, in the years of youth.

- When this indiscriminate defense operates in a relatively pure form the

result may be paradigmatic schizophrenia, recognized clinically as disorganized

(hebephrenic) schizophrenia.

When other defenses and restitutive efforts play a

larger role other clinical pictures may arise.

For example, in catatonic

schizophrenia "freezing," unwittingly "playing dead," may

serve to prevent mad interactions. After a period of mutism, a catatonic

symptom, Anna said: "Considering how crazy I was it was fortunate I didn't

speak."

-

All kinds of psychosis, not only schizophrenia, involve a breakdown of

the I-dynamism, with loss (more or less) of the distinction between Self

and World and a loss of insight.

In nonschizophrenic psychoses the tendency to empathic identification and self-reflection is present to heal the mind

whenever the influence causing mental disorder abates.

Schizophrenia, by

contrast, in our view, is characterized by a defense against that very tendency.

In schizophrenia the mind turns against its potential for relatedness; it fights its top integrating function, the I(nner You).

That may explain why the

prognosis in schizophrenia is, in general, worse than in other kinds of

functional psychosis.

However, any psychosis may lead to such a loss of faith

and trust that the person resorts to the schizophrenic defense. Then the vicious

circle and the diagnosis of schizophrenia take over.

- In the present essay, as often in the literature,

the term frontal lobe means the prefrontal cortex only (Fig. 3).

Since frontal functions depend specifically on certain parts of the basal ganglia and of the thalamus, these

subcortical components are included under the

term the (pre)frontal system.

So, when we speak of functions of the frontal lobe, it should be kept in mind

that we may really be speaking of (pre)frontal system functions.

- Journal of Psychiatric Research, Vol. 8 (1971) pp.

167-187. See also W. J. H Nauta and M. Feirtag, Fundamental Neuroanatomy

(Freeman, 1986).

- In XIX International Congress of Psychology (British

Psychological Society, 1971) pp. 37-52. See also A. R. Luria, The Working

Brain (Penguin, 1973).

- B. Milner and M. Petrides, "Behavioral Effects of

Frontal Lobe Lesions in Man," Trends in NeuroSciences, Vol. 7

(November, 1984) pp. 403-407.

- D. R. Weinberger, K. F. Berman and R. F. Zec,

"Physiologic Dysfunction of Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in

Schizophrenia," Archives of General Psychiatry, Vol. 43 (1986) pp.

114-124.

- The Brain's Record of Auditory and Visual

Experience," Brain, Vol. 86, Part 4 (December, 1963) pp. 595-696.

-

In a series of papers Roger W. Sperry has argued that consciousness,

interpreted as a dynamic, emergent, holistic property of cerebral activity,

exercises superordinate causal control in the brain. See "A modified

concept of consciousness," Psychological Review, Vol. 76, No. 6 (1969) pp.

532-536; and remarks under "Progress on Mind-

Brain Problem" in Sperry's Nobel Prize lecture "Some Effects of

Disconnecting the Cerebral Hemispheres," Science, Vol. 217 (September 24,

1982) pp. 1223-1226.

Critics

− for example, M. S. Gazzaniga and J. E. LeDoux, The Integrated Mind (Plenum 1978) p. 141

− have pointed out that Sperry's viewpoints do not mean insight

into the mechanism, the "how" of consciousness.

The present essay may

be seen as an attempt to give more concrete form to Sperry's suggestions.

- P. M. Coons, E. S. Bowman and V. Milstein,

"Multiple Personality Disorder: A Clinical Investigation of 50

Cases," The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, Vol. 176, No. 9

(1988) pp. 519-527.

- Auditory hallucinations are common in multiple personalities. Since these

hallucinations often emanate from alternate persons they − like the

voices in schizophrenia − may be seen as expressions of

unconscious intentional dynamisms that insist on autonomy.

Hallucinations of

multiple personalities are experienced, however, as "inner voices."

They are not taken as real. Since the I-dynamism reigning at any time in a

multiple personality is whole and closed (not broken as in schizophrenia − cf. Fig.4. Hallucinations) the

distinction between Self and World and the critical attitude are preserved. Therefore the person can tell that the voices are of the mind and not of the

world.

(To

Table of Contents)

© 1989: Lars Martensson. All rights to reprint and use this paper are reserved

by the author.

To

Top

|